Listen to an audio file of this tool.

Now Is the Right Time!

As parents or those in a parenting role, you play an essential role in your child’s success. There are intentional ways to grow a healthy parent-child relationship, and helping your 6-year-old child learn to deal with their most upsetting feelings constructively provides a perfect opportunity.

Children ages 5-10 are in the process of learning about their strong feelings. They do not understand the full-body takeover that can occur when they are angry, hurt, or frustrated. A sense of a lack of control can be scary and add to the length and intensity of their upset.

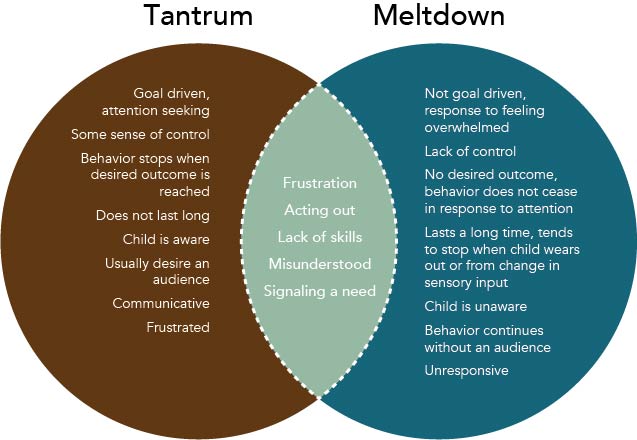

Tantrums and meltdowns can be overwhelming for children and the adults in their lives. Learning how to deal with anger or upset without choosing destructive responses is critical. And, understanding the difference between a tantrum and a meltdown will help parents properly guide their children through these intense times. Your support and guidance matter greatly.

Even though they may look like the same behaviors, tantrums and meltdowns are different and require different approaches to handle each.

Tantrums are

- a normal reaction or outburst to feeling anger or frustration,

- a cry for attention or an inability to communicate,

- within a child’s scope of awareness and control, and

- goal oriented.

A child throwing a tantrum is experiencing intense feelings and acting out in hopes of a desired outcome. Sensory meltdowns, like tantrums, are characterized by a child experiencing big feelings, but the difference is the child is not acting out in search of a desired outcome.

Meltdowns are

- most common among children with sensory processing disorders, autism, or other medical issues who are easily overstimulated or lack the ability to cope with emotional triggers such as fear or anxiety;

- an instinctive survival reaction to being overstimulated or feeling distressed;

- not goal oriented, meaning they are not affected by a reward system;

- long lasting; and

- children may never grow out of them like they do tantrums.

While to a parent or someone in a parenting role, both tantrums and meltdowns may feel like their child is acting out in mischievous behaviors that they need to curb immediately, it is critical to remember that these outbursts are a child’s attempt to communicate something about the intense feelings they have inside. Parents and those in a parenting role can help guide their children through these feelings and teach them skills to manage them.

Parents’ recognition and understanding of both tantrums and meltdowns are essential for teaching children how to recognize and handle their big feelings .

This tool is most applicable to parents handling children with tantrums. While many of the strategies for tantrums are useful for helping children experiencing meltdowns, it is important to note that meltdowns require immense patience, calm, and presence of mind to keep children safe. There are many helpful resources for parents of children with sensory processing challenges. A few resources about sensory meltdowns include:

- Autism Speaks website has multiple articles and information on meltdowns. A simple search of “meltdowns” in the search bar brings up numerous options. https://www.autismspeaks.org/

- National Autistic Society, an organization in the United Kingdom, has a website that also provides multiple articles on meltdowns and dealing with anger and anxiety when “meltdowns” is searched. https://www.autism.org.uk/

- Total Spectrum, an organization specializing in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapies, shared “5 Effective Strategies for Calming Tantrums and Meltdowns” on their website blog. https://www.totalspectrumcare.com/5-effective-strategies-for-calming-tantrums-and-meltdowns/

- A Sensory Life website has an informational section on “Sensory Meltdowns.” https://asensorylife.com/sensory-meltdowns.html

Research confirms that when children learn to manage their feelings, it simultaneously strengthens their executive functions.1 They are better able to use self-control, to problem solve, and focus their attention. This directly impacts their school success.

The key to many parenting challenges, like tantrums, is finding ways to communicate so that both your needs and your child’s needs are met. The steps below include specific, practical strategies along with effective conversation starters to prepare you to help your child work through their roughest, most intense emotional times in ways that build up their resilience and skills for self-management.

Why Tantrums?

Whether it’s your five-year-old’s frustration over trying to get shoes on by themself or your ten-year-old staying up late angry that a friend refused to play with them, learning how to deal with anger, upset, and their many accompanying feelings can become a regular challenge if you don’t create plans and strategies for managing them.

Today, in the short term, learning to manage tantrums can create

- a sense of confidence that you can help your child regain calm and focus,

- a greater opportunity for connection and enjoyment as you work together to care for each other,

- trust in each other that you have the competence to manage your intense feelings, and

- added daily peace of mind.

Tomorrow, in the long term, your child

- builds skills in self-awareness;

- builds skills in self-control and managing emotions;

- learns independence, life skills competence, and self-sufficiency; and

- builds assertive communication to communicate needs and boundaries, which are critical for keeping them safe and ready to deal with peer pressure.

Five Steps for Managing Tantrums

This five-step process helps you and your child manage tantrums. It also builds important skills in your child. The same process can be used to address other parenting issues as well (learn more about the process).

Tip

Tip

These steps are done best when you and your child are not tired or in a rush.

Tip

Tip

Intentional communication and a healthy parenting relationship support these steps.

Step 1. Get Your Child Thinking by Getting Their Input

You can get your child thinking about ways to manage their most upsetting feelings constructively by asking them open-ended questions. You’ll help prompt your child’s thinking. You’ll also begin to better understand their thoughts, feelings, and challenges related to managing their intense feelings, so that you can address them. In gaining input, your child

- has the opportunity to become more aware of how they are thinking and feeling and understand when the cause of their upset is anger related;

- can think through and problem solve any challenges they may encounter ahead of time;

- has a greater stake in anything they’ve thought through and designed themselves, and with that sense of ownership, comes a greater responsibility for implementing new strategies;

- will have more motivation to work together and cooperate because of their sense of ownership; and

- will be working with you on making decisions (and understanding the reasons behind those decisions) about critical aspects of their life.

Actions

- Be curious about your child’s feelings. You might start by asking:

- “When do you feel angry or intensely upset?”

- “What time of day?”

- “What people, places, and activities are usually involved?”

- Use your best listening skills. Remember, what makes a parent angry can differ greatly from what angers a child. Listen closely to what is most concerning to your child without projecting your own thoughts, concerns, and feelings.

- Explore the mind-body connection. In calmer moments with your child, ask, “How does your body feel now?” See how descriptively they can list their physical signs of wellbeing. Now ask, “How does your body feel when you are angry?” For every person, their physical experience will be different. Find out how your child feels and make the connection between those symptoms and the normal feelings they are having.

Tip

Tip

If your child has recently thrown a tantrum, use that example to reflect on what caused it at a time when you are both calm. You might ask, “What made you so upset after school a few days back?” Finding out what contributed to a tantrum can give you insight into your child’s triggers and also help raise your child’s self-awareness.

Step 2. Teach New Skills by Interactive Modeling

Because intense feelings like anger and hurt occur as you go about your daily life, you may not consider their role and impact on your child though it can have a major influence on their day and your relationship with them. Learning about what developmental milestones a child is working on can help you better understand what your child is going through and what might be contributing to anger or frustration.2

- Five-year-olds are working hard to understand how things work, so they tend to ask lots of questions and appreciate explanations. They may struggle to see others’ perspectives. They are working hard to understand rules and may be upset or disappointed when they do not understand a rule or struggle to show competence. They may get angry if they break a rule or if they see others breaking a rule. They are also beginning to test rules as they move from five to six, which can prompt a parent’s anger.

- Six-year-olds can feel anxious as they want to do well in school and at home. They may be highly competitive and criticize peers while being sensitive to being criticized themselves. They care about friendships and may experience upset feelings related to those relationships.

- Seven-year-olds need consistency and may get angry and feel out of control when schedules are chaotic and routines change. They may be moody and require reassurance from adults. They take school and homework seriously and may even feel sick from worrying about tests or assignments. They can take academic failure personally and get angry and push away or neglect their work to avoid more failure.

- Eight-year-olds have interest and investment in friendships. Peer approval becomes as important as their teacher’s approval. Peer approval can create upset when they are rejected by friends. They are more resilient when they make mistakes. They have a greater social awareness of local and world issues, so they may be concerned about the news or events outside of your community.

- Nine-year-olds can be highly competitive and critical of themselves and others. They may worry about who is in the “in” and “out” crowds and where they fit in friendship groups. They may tend to exclude others in order to feel included in a group, so it’s a good time to encourage inclusion and kindness toward a diverse range of others. They are just beginning puberty. They will be experiencing growth spurts and the associated clumsiness and awkwardness. Anger can be generated from rejection or judgment from peers.

- Ten-year-olds have an increased social awareness and try to figure out the thoughts and feelings of others. With this awakening comes a newfound worry about what peers are thinking of them (for example, “He’s staring at me. I think he doesn’t like me.”). They can become angered if they feel judged even if they are not making accurate predictions of peers’ feelings. They are also seeking more independence from parents so they can get angry when parents either treat them as they were treated in younger years or make them feel dependent (taking some of their power away).

Teaching is different than just telling. Teaching builds basic skills, grows problem-solving abilities, and sets your child up for success. Teaching also involves modeling and practicing the positive behaviors you want to see, promoting skills, and preventing problems.

Actions

- Learn together! Anger and hurt are important messages to pay attention. They mean emotional, social, or physical needs are not getting met or necessary boundaries (rules, values) are being violated. It’s important to ask: “Why am I feeling this way? What needs to change in order to feel better?”

- Respond with emotional intelligence. When your child has a tantrum, focus on calming yourself down and then your child. Stop what you are doing and walk them, if you can, to a safe, non-public spot where they can calm down. Don’t leave them. Be with them and using a calm, soft voice, encourage them to breathe by breathing with them slowly. Don’t try and talk about the situation until they are calm (they won’t be able to hear you anyway). Stand aside and focus on your own deep breathing while you allow your child time to calm down.

- Brainstorm coping strategies. There are numerous coping strategies you and your child can use depending on what feels right. But, when you are really angry and upset, it can be difficult to recall what will make you feel better. That’s why brainstorming a list, writing it down, and keeping it at the ready can come in handy when your child really needs it. Here are some ideas from Janine Halloran:3 imagine your favorite place, take a walk, get a drink of water, take deep breaths, count to 50, draw, color, and build something.

- The saying “name it to tame it” really works! Look for ways to identify feelings and name them. Post this feelings chart on your refrigerator as a helpful reminder. The more you can name a range of feelings in family life, the more comfortable your child will get with saying what they are feeling. This one strategy alone can reduce the time a child is engaged in a tantrum since they become skilled at saying what they are feeling and feel more capable of securing your understanding faster.

- Create a calm down space. During a playtime or time without pressures, design a “safe base,” or place where your child decides they would like to go when they are upset to feel better. Maybe their calm down space is a beanbag chair in their room, a blanket, or special carpet in the family room. Then, think together about what items you might place there to help with the calm down.

- Teach your child how to stop rumination. If you catch your child uttering the same upsetting story more than once, then your child’s mind has hopped onto the hamster wheel of rumination. In these times, it can be difficult to let go. Talk to your child about the fact that reviewing the same concerns over and again will not help them resolve the issue, but talking about them might help, calming down might help, and learning more might help. Setting a positive goal for change will help. Practice what you can do when you feel you are thinking through the same upsetting thoughts.

- When you notice the same upset running through your mind, say “Stop!” out loud. Then, try out one of your coping strategies to help you feel better and let go of those nagging thoughts. Encourage your child to try it.

- Reflect on your child’s anger so you can be prepared to help. When you are reflecting on your child’s feelings, you can think about unpacking a suitcase. Frequently, there are layers of feelings that need to be examined and understood, not just one. Anger might just be the top layer. So, after you’ve discovered why your child was angry, you might ask about other layers. Was there hurt or a sense of rejection involved? Perhaps your child feels embarrassed? Fully unpacking the suitcase of feelings will help your child feel better understood by you as they become more self-aware. Ask yourself:

- “What needs is my child not getting met?” They might be needing a friend to listen, needing some alone time, or needing to escape a chaotic environment.

- “Can the issue be addressed by my child alone or do they need to communicate a need, ask for help, or set a boundary?” One of the hardest steps to take for many can be asking for help or drawing a critical boundary line when it’s needed. You’ll need to help find out what those issues are in your reflections with your child. But then, guiding them to communicate their need is key.

- Help your child repair harm when needed. A critical step in teaching your child about managing anger is learning how to repair harm when they’ve caused it. Mistakes are a critical aspect of their social learning. Everyone has moments when they hurt another. But, it’s that next step that they take that matters in repairing the relationship.

- Find small opportunities to help your child mend relationships. Siblings offer a regular chance to practice this! If there’s fighting, then talk to your child about how they feel first. When you’ve identified that they had a role in causing harm, brainstorm together how they might make their sibling feel better. You might ask, “What could you do?”

- Allow your child to supply answers and you may be surprised at how many options they generate. Support and guide them to follow through on selecting one and doing it.

- Tantrums occur at any age. Though you may not call it a tantrum beyond toddler or preschool age, children, teens, and adults alike can emotionally lose control.

- Anger is not bad or negative. You should not avoid or shut down the experience of it. There’s a good reason for anger. However, everyone has experienced someone in their lives who has lost control and acted in ways that harmed themself or others when angry. Every feeling, including anger, serves a critical purpose. Anger provides essential information about a person, what emotional or physical needs are not getting met, and where their boundaries lie. Understanding intense feelings is key to helping your child better understand themselves and learn healthy ways to manage their intense feelings.1

- Expressing anger in a manner like yelling will not dissipate it. In fact, research confirms that the expression of aggression whether it’s yelling or hitting (and that includes hitting, yelling, or spanking by parents) exacerbates the anger.1

- Venting such as complaining, ranting, or even mumbling does not get out the upset thoughts and feelings. In fact, venting is to anger as rumination is to worry. You can churn through worrying thoughts in your mind repeatedly, but those thoughts go nowhere and ultimately are unproductive. So too venting, whether you are listing off your complaints to another or talking to yourself, tends to reinforce negative thinking because it does not offer an alternative view of the situation nor does it pose any solutions.

- Avoiding or pretending you are not angry will not make it go away in time. Because anger – like any other feeling – is emerging to send a vital message to its owner, it cannot be avoided or denied. When turned inward, that anger can become destructive in the body. Also, when anger is buried, it can be stuffed down for a time but may contribute to a larger explosion (that may not have occurred otherwise) because of the buildup of heated feelings over time.

Tip

Tip

Raising your voice and your level of upset in response to your child’s tantrum will only increase the intensity and duration of your child’s upset. Yelling only communicates that you are raising the level of emotional intensity not diminishing it. Leaving your child alone in their room will also escalate the tantrum at this age. They need you, and they may be fearful of themselves because they have literally been overpowered by their own feelings.

Tip

Tip

The only way a calm down space serves as a tool for parents to promote their children’s self-management skills is if they allow a child to self-select the calm down space. Practice using it and gently remind them of it when they are upset. “Would your calm down space help you feel better?” you might ask. But if that space is ever used as a punishment or a directive – “Go to your calm down space!” – the control lies with the parent and no longer with the child, and the opportunity for skill building is lost.

Trap

Trap

If you tell or even command your child to make an apology, how will they ever learn to genuinely apologize with feeling? In fact, apologizing or making things right should never be assigned as a punishment since then the control lies with the adult and robs the child of the opportunity to learn the skill and internalize the value of repairing harm. Instead, ask the child how they feel they should make up for the hurt they’ve caused and help them implement their idea.

Step 3. Practice to Grow Skills and Develop Habits

Practice is necessary for children to internalize new skills. Practice can take the form of pretend play, cooperatively completing the task together, or trying out a task with you as a coach and ready support. Practice grows vital new brain connections that strengthen (and eventually form habits) each time your child manages their intense feelings.

Practice also provides important opportunities to grow self-efficacy — a child’s sense that they can manage their feelings successfully.

Actions

- Use “Show me…” statements. When a child learns a new ability, they are eager to show it off! Give them that chance. Say, “Show me how you use your safe base to calm down.” This can be used when you observe their upset mounting.

- Recognize effort by using “I notice…” statements like, “I noticed how you took some deep breaths when you got frustrated. That’s excellent!”

- Accept feelings. If you are going to help your child become emotionally intelligent in managing their biggest feelings, it is important to acknowledge and accept their feelings — even ones you don’t like! When your child is upset, consider your response. You could say, “I hear you’re upset. What can you do to help yourself feel better?”

- Practice deep breathing. Because deep breathing is such a simple practice that can assist your child anytime, anywhere, it’s important to get plenty of practice so that it becomes easy to use when needed. Here are some enjoyable ways to practice together!4

- Teddy Bear Belly Breathing. Balance a teddy bear on your child’s tummy and give it a ride with the rising and falling of their breath. This would be ideal to practice during your bedtime routine when you are lying down and wanting to calm down for the evening.

- Blowing Out Birthday Candles Breathing. You can pretend you are blowing out candles on a birthday cake. Just the image in your head of a birthday cake brings about happy thoughts. And, in order to blow out a number of small flames, you have to take in deep breaths.

- Play turtle. The Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies curriculum encourages children to pretend they are a turtle. When they are upset, they can sink back into their shells (they can place their arms over their head) and breathe inside the shelter of their own arms to regain calm before re-entering their environment. This could inspire wonderful play with young children and stir their vivid imagination of what it might look like and feel like when they are calming down.

- Include reflection on the day in your bedtime routine. You might ask, “What happened today that made you happy?” or “What were the best moments in your day?” You should answer the questions as well. Children may not have the chance to reflect on what’s good and abundant in their lives throughout the day. Grateful thoughts are a central contributor to happiness and wellbeing.

- Reflect and reframe. When you are reflecting with your child about their upset, it can be helpful to consider the issue from another perspective. Though you never want to excuse another child’s hurtful behaviors, you can understand their thoughts and feelings better. For example, Julie was cruel to your child today when, on most days, they are joyful friends. You might ask, “Do you know if anything is going on at home or at school that might be upsetting to Julie?” Find out. What if Julie’s parents have recently announced they are getting a divorce? There are always reasons for children’s behavior. See if you can dig further to find compassion and understanding and share that with your child.

- If your child has acted in ways that part with your family’s values, be sure and reflect on those, such as, “In our family, we choose never to hit another person or cause physical harm. What could you have done instead?”

Trap

Trap

Refrain from judging your child’s friends. You want your child to trust you with their friendship worries and problems. If you harshly judge their friends, they may lose some of that trust and may not confide in you.

Tip

Tip

Have you seen the tiny Guatemalan Worry Dolls that you tell your worries to before going to bed and then, they take on your worries for you so you will be relieved of them and can sleep? Use this wonderful concept with your children. Assign a few stuffed friends or favorite action figures the job! Addressing worries can help alleviate feelings that are compounding and may be building up to an explosion.

Step 4. Support Your Child’s Development and Success

At this point, you’ve taught your child some new strategies for managing their intensely upset feelings so that they understand how to take action. You’ve practiced together. Now, you can offer support when it’s needed by reteaching, monitoring, coaching, and when appropriate, applying logical consequences. Parents naturally offer support as they see their child fumble with a situation in which they need help. This is no different.

Actions

- Ask key questions to support their skills. For example, “You are going to see Julie today. Do you remember what you can do to assert your feelings?”

- Learn about your child’s development. Each new age presents different challenges. Being informed about what developmental milestones your child is working toward will offer you empathy and patience.

- Stay engaged. Working together on ideas for trying out new and different coping strategies can help offer additional support and motivation for your child when tough issues arise.

- Apply logical consequences when needed. Logical consequences should come soon after the negative behavior and need to be provided in a way that maintains a healthy relationship. Rather than punishment, a consequence is about supporting the learning process. First, get your own feelings in check. Not only is this good modeling, when your feelings are in check you are able to provide logical consequences that fit the behavior. Second, invite your child into a discussion about the expectations established in Step 2. Third, if you feel that your child is not holding up their end of the bargain (unless it is a matter of them not knowing how), then apply a logical consequence as a teachable moment.

Step 5. Recognize Effort and Quality to Foster Motivation

No matter how old your child is, your praise and encouragement are their sweetest reward.

If your child is working to grow their skills – even in small ways – it will be worth your while to recognize it. Your recognition can go a long way to promoting positive behaviors and helping your child manage their feelings. Your recognition also promotes safe, secure, and nurturing relationships — a foundation for strong communication and a healthy relationship with you as they grow.

You can recognize your child’s efforts with praise, high fives, and hugs. Praise is most effective when you name the specific behavior you want to see more of. For example, “You took a deep breath when you got frustrated– that is a great idea!”

Avoid bribes. A bribe is a promise for a behavior, while praise is special attention after the behavior. While bribes may work in the short term, praise grows lasting motivation for good behavior and effort. For example, instead of saying, “If you include your sister in the game, I will let you choose the game we play after dinner” (which is a bribe), try recognizing the behavior after. “You worked hard to include your sister. Love seeing that!”

Actions

- Recognize and call out when it is going well. It may seem obvious, but it’s easy not to notice when all is moving along smoothly. When your child is using the self-management tools you’ve taught them, a short, specific call out is all that’s needed. “I noticed when you got frustrated with your homework, you moved away and took some deep breaths. Yes! Excellent.”

- Recognize small steps along the way. Don’t wait for the big accomplishments – like an entire day with no tantrums – in order to recognize effort. Remember that your recognition can work as a tool to promote more positive behaviors. Find small ways your child is making an effort and let them know you see them.

- Build celebrations into your routine. For example, after your child recovers from a time of frustration faster and in better control, celebrate by snuggling together and reading before bed. Or in the morning, once ready for school, take a few minutes to watch a favorite cartoon together. Include hugs, high fives, and fist bumps as ways to appreciate one another.

Closing

Engaging in these five steps is an investment that builds your skills as an effective parent to use on many other issues and builds important skills that will last a lifetime for your child. Throughout this tool, there are opportunities for children to become more self-aware, to deepen their social awareness, to exercise their self-management skills, to work on their relationship skills, and to demonstrate and practice responsible decision making.