Listen to an audio file of this tool.

Now Is the Right Time!

Children and adults alike experience stress. Stress is typically caused by an external trigger like an angry sibling shouting, “You can’t have my game!” or a mom insisting a child needs to stop playing and work on a homework assignment they’ve been avoiding. Feelings of stress are naturally built-in mechanisms for human survival and thriving. These feelings are the body’s way of warning you when there is danger and calling your attention to problems that need resolving. As a parent or someone in a parenting role, you can help your child learn to identify and manage their stress — an important skill they will use throughout their lives.

Children ages 5-10 are in the process of learning about their strong feelings, understanding the rules of school, growing friendships, and learning to master new concepts in reading, math, and more. All these new experiences and expectations for their performance can cause stress that is typical for all children.

In addition, most children also face more intense stress like during a sustained global crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic or through family challenges such as caregivers who divorce, have a mental illness, or deal with addiction. Many families have members who face intense stress due to the effects of systemic oppression, income inequality, lack of access to services, prejudices, stigma, or other injustices. Indeed, the support a child receives from trusted caregivers during and after stress can make a powerful difference in how that child copes and integrates that experience over the long term. With intentional guidance and support, parents and those in a parenting role can advance their children’s development to build their inner strength and resilience.

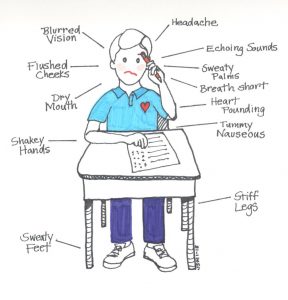

Symptoms of stress may look differently in children than they do in adults. Children can experience both mental and physical symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, irritability, trouble sleeping at night, and stomach and digestive problems. Some children may act out and create power struggles as they have not yet developed the skills to constructively manage their stress.

Symptoms of stress can be very similar to symptoms of anxiety, which can be difficult for parents and those in a parenting role to tell the difference. Even though signs of stress and anxiety may look the same, they are different and require different approaches to handle each. Understanding the differences between stress and anxiety will help parents properly guide their children through their intense feelings.

Stress

- is a normal reaction to a situation or experience (an external trigger or stressor);

- generally goes away when the stressor goes away;

- doesn’t significantly interfere or alter daily functioning and activities; and

- responds well to coping strategies like exercise, deep breathing, etc.

Anxiety

- includes intense and persistent worry and fear that is difficult to control and out of proportion to the situation,1

- can be long lasting, and

- significantly interferes with everyday functioning and activities.

While mild anxiety may respond well to coping strategies used to manage stress, a child experiencing anxiety may require additional help from a mental health professional to determine if they have an anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders are different from feelings of stress or mild anxiety, which are short term.

There are resources listed at the end of this tool to help parents and those in a parenting role address complex issues like adverse childhood experiences; persistent, debilitating anxiety; and depression.

Every child needs to learn to manage stress. The following steps will prepare you to help your child through the kinds of stressors many commonly face. The steps include specific, practical strategies along with effective conversation starters to guide you in helping your child manage stress in ways that develop their resilience and skills for self-management.

Why Stress?

Whether it’s your five-year-old refusing to join in a game with other children because they have never played the game before or your ten-year-old having trouble getting to sleep because they are worried about a test the next day, stress and how to deal with it can become a daily challenge if you don’t create plans and strategies for dealing with it along with input from your child.

Today, in the short term, teaching skills to manage stress can create

- greater opportunities for connection, cooperation, and enjoyment;

- trust in each other that you have the competence to manage your big feelings; and

- added daily peace of mind.

Tomorrow, in the long term, your child

- builds skills in self-awareness,

- builds skills in self-control and managing feelings, and

- develops independence and self-sufficiency.

Five Steps for Managing Stress

This five-step process helps you and your child manage stress. It also builds important skills in your child. The same process can be used to address other parenting issues as well (learn more about the process).

Tip

Tip

These steps are done best when you and your child are not tired or in a rush.

Tip

Tip

Intentional communication and a healthy parenting relationship support these steps.

Step 1. Get Your Child Thinking by Getting Their Input

In order to ask helpful questions of your child and learn about their stress, parents can benefit from understanding how stress is processed in the body and brain. Understanding how the brain — for both adults and children — operates when feeling stressed is critical in shaping your responses and offering support for your child.

You can get your child thinking about ways to manage daily stress by asking open-ended questions. Open-ended questions help prompt your child’s thinking. You’ll also begin to better understand their thoughts, feelings, and challenges related to stress. In gaining input, your child

- develops awareness about how they are thinking and feeling and understands when the cause of their upset is stress related and

- can think through and problem solve challenges they may encounter ahead of time.

Actions

- Engage your child in a conversation to understand your child’s thoughts and feelings. You could ask:

- “When do you feel stressed?”

- “When do you feel uncomfortable, frustrated, or angry?” (These feelings can occur to mask underlying stress.)

- “What time of day?”

- “What people, places, and activities are usually involved?”

- Practice actively listening to your child’s thoughts, feelings, and worries. Though you may want to fix your child’s problem quickly, it’s important to simply listen first. Because parents can have a tendency to project their own worries onto their children when they may be concerned with something different altogether, use your best listening skills! The way to find out whether or not your child is stressed is by offering a safe space for them to talk about their worries without fearing judgment.

- Paraphrase what you heard your child say. Paraphrasing is echoing back to the person a summary of what they’ve said to check how accurate your listening is. It also confirms to your child that you have heard them. A conversation might go something like this:

- Child: “I just found out my classmates are in a secret recess club, and I’m not. They don’t like me.”

- Parent modeling paraphrasing: “So I hear you found out that your classmates have a club at recess that you are not a part of. Is that right?” If you hear a subtext of feeling, as in this example, you can also reflect the feeling implied. Parent reflecting feeling: “I get the sense you are feeling upset about being left out. Is that right?”

- Explore the mind-body connection. In calmer moments with your child, ask, “How does your body feel now?” See how descriptively they can list their physical signs of wellbeing. Now ask, “How does your body feel when you are feeling stress?” For every person, their physical experience will be different. Find out how your child feels and make the connection between those symptoms and the normal feelings they are having.

Tip

Tip

Be sure you talk about stress at a calm time when you are not stressed!

Step 2. Teach New Skills by Interactive Modeling

Because stress is such an integral experience in people’s daily lives, you may not realize how it can influence every aspect of your day. Learning about developmental milestones can help you better understand what your child is working hard to learn.

- Five-year-olds are working hard to understand how things work, so they appreciate explanations, and they ask lots of questions. They have vivid imaginations, which can create worries that parents or those in a parenting role may not understand. Children in this stage may struggle to see others’ perspectives. They are learning rules and want to help, cooperate, and follow them, but may get upset or disappointed when they do not understand a rule. They may also begin to test rules.

- Six-year-olds want to do well in school and at home, which may cause them to feel stress. They may be highly competitive and criticize peers while being sensitive to being criticized themselves. They care about friendships and may have worries related to those relationships. They may be clumsy sometimes and require more time for fine and large motor skill activities.

- Seven-year-olds need consistency and may feel stress more when schedules are chaotic, and routines change. They tend to be moody and require reassurance from adults. They take school and homework seriously and may even feel sick from worrying about tests or assignments.

- Eight-year-olds’ interest and investment in friendships and peer approval becomes as important as the teacher’s approval. They are more resilient when they make mistakes. They have greater social awareness of local and world issues and may be concerned about the news or events outside of your community.

- Nine-year-olds can be highly competitive and critical of themselves and others. They may worry about who is in the “in” and “out” crowds and where they fit in friendship groups. They may exclude others in order to feel included in a group, so it’s a good time to encourage inclusion and kindness toward a diverse range of peers.

- Ten-year-olds have an increased social awareness so that they can try to figure out the thoughts and feelings of others. With this awakening comes a newfound stress about what peers are thinking of them (“He’s staring at me. I think he doesn’t like me.”).

Teaching is different than just telling. Teaching builds basic skills, grows problem-solving abilities, and sets your child up for success. Teaching also involves modeling and practicing the positive behaviors you want to see, promoting skills, and preventing problems.

Actions

- Model the skills yourself, and your child will notice and learn.

- Get exercise and fresh air. Getting active in any way, whether it’s taking a walk or gardening, can help relieve stress.

- Remember to breathe. Try and make a daily routine of taking 5-10 deep breaths to help you begin the morning calm and focused. If you run into stressful situations during the day, remember to breathe deeply in the midst of the chaos to help yourself better cope with it.

- Create quiet time. Busy schedules with children are inevitable. However, everyone needs quiet, unscheduled time to refuel. Say “No” to social commitments when it’s too much. In addition to guarding your children’s quiet time, be certain to carve out your own.

- Set a goal for daily connection. Touch can deepen intimacy in any relationship creating safety, trust, and a sense of wellbeing. It offers health benefits as well. A study found that those who hugged more were more resistant to colds and other stress-induced illnesses.3

- Notice, name, and accept your feelings regularly. You may get in the habit of reassuring family members or friends, “I’m fine,” even when you are not. Yet, you need to be a model of emotional intelligence if your children are to learn to manage their feelings. Notice what you are honestly feeling and name it. “I’m tired and cranky this afternoon.” Accepting those feelings instead of fighting them can be a relief and allow you to take action toward change.

- Ask, “What is my child developmentally ready to try?” Allow for healthy risks. Realize it will not always be done perfectly or in the ways you expect. Trust your child’s ability to solve their own problems with your loving support.

- Brainstorm coping strategies. There are numerous coping strategies you and your child can use depending on what feels right. But when you are feeling stress, it can be difficult to recall what will make you feel better. That’s why brainstorming a list, writing it down, and keeping it at the ready can come in handy when your child really needs it. For example, your child could imagine a favorite place, take a walk, get a drink of water, take deep breaths, count to 50, draw, color, or build something. For an easy-to-print illustration, check out Confident Parents, Confident Kids’ Coping Strategies for K-4.

- Design a plan. When you’ve learned about what happens in your brain and body when stress takes over, you know you need a plan so you don’t have to think at that moment. What will you say when really upset? Where will you go?

- Work on your child’s feelings vocabulary. Yes, at times, parents and those in a parenting role have to become a feelings detective. If your child shuts down and refuses to tell you what’s going on, you have to dig for clues. Though your child has been speaking for some time now, they take longer to develop their feelings vocabulary. That’s because they hear feelings expressed in daily conversations much less frequently than thoughts or other expressions. Being able to identify feelings is the first step to being able to successfully manage feelings.

- Create a calm down space. During a playtime or time without pressures, design a “safe base” or place where your child decides they would like to go to when upset to feel better. Maybe their calm down space is a beanbag chair in their room, a blanket, or special carpet in the family room. Then, think through together what items you might place there to help them calm down.

- Is your child uttering the same upsetting story more than once, or repetitively analyzing problems or concerns? Talk to your child about the fact that reviewing the same concerns over and again will not help them resolve the issue. Talking about them might help, calming down might help, and learning more might help. Setting a positive goal for change will help. Practice what you can do when you feel you are thinking through the same upsetting thoughts.

- Create a family gratitude ritual. People get plenty of negative messages each day through the news, performance reviews at school or work, and through challenges with family and friends. It can seem easier to complain than to appreciate. Balance out your daily ratio of negative to positive messages by looking for the good in your life and articulating it. Model it and involve your children. This is the best antidote to a sense of entitlement or taking your good life for granted while wanting more and more stuff. Psychologists have done research on gratefulness and found that it increases people’s health, sense of wellbeing, and their ability to get more and better sleep at night.4

Tip

Tip

Deep breathing is not just a nice thing to do. It actually decreases the chemical that has flowed over your brain and allows you to regain access to your creativity, language, and logic versus staying stuck in your primal brain. Practicing deep breathing with your child can offer them a powerful tool to use anytime, anywhere when they feel overcome with stress.

Step 3. Practice to Grow Skills, Confidence, and Develop Habits

Your daily conversations can be opportunities for your child to practice vital new skills if you seize those chances. Practice grows vital new brain connections that strengthen (and eventually form habits) each time your child works hard to practice essential stress management skills.

Practice also provides important opportunities to grow self-efficacy — a child’s sense that they can do a task or skill successfully. This leads to confidence. It will also help them understand that mistakes and failures are part of learning.

Actions

- Use “Show me…” When a child learns a new ability, they are eager to show it off! Give them that chance. Say, “Show me how you use your safe base to calm down.” This can be used when you observe their stress mounting.

- Practice your plan! Be sure and try out your plan for managing stressful situations in smaller scale ways. In other words, could you do a dry run — walk to school and be in the environment to act out your plan before kids arrive for school? This kind of dry run practice can make all of the difference in assisting your child when their toughest times arise.

- Recognize effort by using “I notice…” statements like, “I notice how you took some deep breaths when you got frustrated. That’s excellent!”

- Include reflection on the day in your bedtime routine. Begin by asking about worries or problems that your child will surely consider after you leave the room. Listen and offer comfort. Demonstrate that you are allowing and accepting the uncertainty of unresolved problems. You could say, “There’s no amount of worrying that is going to fix things tonight. So how can you talk about accepting what you have and where you are now and working on it tomorrow?” Then, turn to gratitude. Children may not have the chance to reflect on what’s good and abundant in their lives throughout the day, yet grateful thoughts can be a central contributor to happiness and wellbeing. And, grateful thoughts directly wipe out ruminations. So ask, “What happened today that made you happy?” or “What were the best moments in your day?”5

- Proactively remind. Remind in a gentle, non-public way. You may whisper in your child’s ear, “Remember what we are going to say when we keep playing worries over and again in our mind? What is it?”

Step 4. Support Your Child’s Development and Success

At this point, you’ve taught your child some new strategies for managing stress so that they understand how to take action. You’ve practiced together. Now, you can offer support when it’s needed by reteaching, monitoring, and coaching. Parents naturally offer support as they see their child fumble with a situation in which they need help. This is no different.

Actions

- Ask key questions to support their skills. For example, “You have a test coming up today. Do you remember what you can do to help yourself if you feel stressed?”

- Learn about development. Each new age will present differing challenges and along with them, stress. Becoming informed regularly about what developmental milestones your child is working toward will offer you empathy and patience.

- Reflect on outcomes. “Seems like you couldn’t get to sleep last night because you had so much on your mind. Did you have a hard time paying attention in class? What could we do tonight to help?”

- Stay engaged. Working together on ideas for trying out new and different coping strategies can help offer additional support and motivation for your child when tough issues arise.

Step 5. Recognize Effort and Quality to Foster Motivation

No matter how old your child is, your praise and encouragement are their sweetest reward.

If your child is working to grow their skills — even in small ways — it will be worth your while to recognize it. Your recognition can go a long way in promoting positive behaviors and helping your child manage their feelings. Your recognition also promotes safe, secure, and nurturing relationships — a foundation for strong communication and a healthy relationship with you as they grow.

Actions

- Recognize and call out when it is going well. It may seem obvious, but it’s easy not to notice when all is moving along smoothly. When children are using the self-management tools you’ve taught them, a short, specific call out is all that’s needed: “I noticed when you got frustrated with your homework, you moved away and took some deep breaths. Yes! Excellent.”

- Recognize small steps along the way. Remember that your recognition can work as a tool to promote more positive behaviors. Find small ways your child is making an effort and let them know you see them.

- Build celebrations into your routine. For example, “We’ll get our bedtime routine finished first, and then we can snuggle up to a good book and talk about our reflections from the day.” Include hugs in your repertoire of ways to appreciate one another.

Closing

Engaging in these five steps is an investment that builds your skills as an effective parent to use on many other issues and builds important skills that will last a lifetime for your child. Throughout this tool, there are opportunities for children to become more self-aware, to deepen their social awareness, to exercise their self-management skills, to work on their relationship skills, and to demonstrate and practice responsible decision making.

Additional Resources for More Intense Forms of Stress — Adverse Childhood Experiences, Anxiety, and Depression

If there are high emotions in your household most days, most of the time, then it may be time to consider outside intervention. Physical patterns (like anxiety or depression) can set in that require the help of a trained professional. Seeking help from a mental health professional is the same as going to your doctor for a physical ailment. It is very wise to seek outside help. The following are some U.S.-based resources to check out.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP)

- Has definitions, answers to frequently asked questions, resources, expert videos, and an online search tool to find a local psychiatrist. http://www.aacap.org

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Healthy Children

- Provides information for parents about emotional wellness, including helping children handle stress, psychiatric medications, grief, and more. http://www.healthychildren.org

- American Psychological Association (APA)

- Offers information on managing stress, communicating with kids, making stepfamilies work, controlling anger, finding a psychologist, and more. http://www.apa.org

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT)

- Provides free online information so that children and adolescents benefit from the most up-to-date information about mental health treatment and can learn about important differences in mental health supports. Parents can search online for local psychologists and psychiatrists for free. http://www.abct.org